Trends in sea surface temperature at Townsville, Great Barrier Reef, Queensland

Dr. Bill Johnston[1]

(scientist@bomwatch.com.au)

Main points

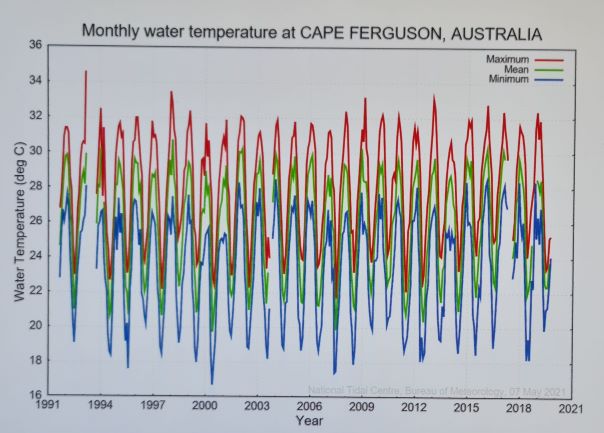

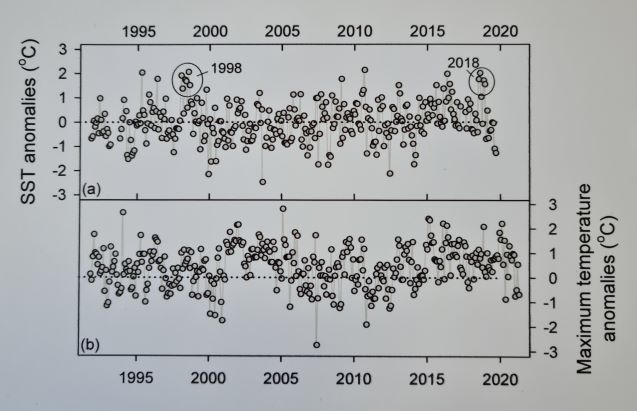

#1. Heat exchanges with the landscape bias trends in sea surface temperature (SST) measured close to shore such as at Cape Ferguson near Townsville (Latitude -19.2774o, Longitude 147.0586o), especially during periods of low summer rainfall when maximum temperature (Tmax) is axiomatically higher. Removing seasonal cycles, which show no trend, and accounting for the significant effect of terrestrial Tmax and barometric pressure (hPa), left no trend of change attributable to any other factor. While Tmax is clustered into dry-warm and moist-cool years, there is no evidence that SST has warmed since records commenced in September 1991.

#2. At Cape Ferguson SST cools more slowly from its peak in January to July than it warms from August to to December. Great Barrier Reef (GBR) ecosystems must therefore be adapted to the 8.1C interannual cycle and average month-to-month SST changes of up to 2C.

#3. Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) SST data is short, patchy, poorly dispersed towards the extremities of the Reef and not useful for estimating trend. Selecting day-of-year averages for 27 sites extending from Thursday Island Cape York to North Solitary Island in the south showed Reef ecosystems are adapted to average temperatures between 27C to greater than 29C and greater than 30C for four to five months, and less than 20C in winter (July to September). Highest average SST is predicted to be 29.64C ( ±PI 1.12oC) at Latitude ‑13.5o in late January; SST cools slightly towards the equator.

#4. The Southern Equatorial Current which splits to form the North Queensland current and the East Australian Current (which dissipates south into the Tasman Sea) is cooled continuously by convection, long-wave re-radiation to space by towering clouds, cool rainfall and the formation of reflective residual cirrus ice-clouds. These processes maintain SST within close limits that rarely and only transiently exceed 30oC.

#5. No difference was found between temperatures measured between Port Stephens and Cape Sidmouth in November and December 1871 and data for those times derived from AIMS datasets. Further, data does not support claims by AIMS, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, The Australian Museum, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation and groups including WWF and the Climate Council that sea surface temperature has increased by an unremarkable 0.8oC or that continued warming is likely to threaten survival of the Reef.

#6 Near the Equator the water cycle operates as a self-regulating heat-pump that catapults moisture high into the atmosphere to form cloud that reflects or rejects incoming solar energy during the monsoon and thereby limits input of warm waters to the North Queensland and East Australian currents. There is no evidence that the process has broken-down or is likely to break down in the future.

Background

With operations in Townsville, Darwin and Perth, AIMS is part of arguably the largest, most expensive and elite conglomerate of research institutions in Australia. Spread across multiple universities and state and commonwealth agencies and with strong support from the Australian Research Council, their research focuses on the effect of climate change on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. They and partner organisations including CSIRO and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), Great Barrier Reef Foundation, WWF and the Climate Council have consistently claimed survival of the Reef is imperiled by rising seas and anthropogenic warming. For instance, GBRMPA states unequivocally[2] that “Australia’s climate has warmed on average by 1.44 degrees Celsius since national records began in 1910, with most warming occurring since 1950 and every decade since then being warmer than the ones before”; and that “sea surface temperatures in the Australian region have warmed by around 1 degree Celsius since 1910, with the Great Barrier Reef warming by 0.8 degrees Celsius in the same period”.

Research reported here investigates that claim. The main question is:

- Is mean SST increasing, and if so, at what rate.

What we did

Using average SST data from September 1991 for the fixed tide gauge at Cape Ferguson, which is part of the Australian baseline Sea Level Monitoring Project run by Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), we aimed to distinguish between variables that caused variation IN SST from latent factors that may have impacted ON the data-stream (impact variables). Multiple linear regression (MLR) was used to investigate variation IN SST, while factors that impacted ON the data-stream were investigated using step-change analysis of MLR residuals (SST with covariable effects removed).

Commencing on 28 November 1871, SST was measured between Port Stephens and Cape Sidmouth near the top of Cape York by astronomers from Melbourne and Sydney who sailed on the Governor Blackall to observe the total eclipse of the sun and also on their return voyage commencing 13 December. They used bucket samples taken near the bow of the steamer each hour between 6 am and 6 pm each day. Data were summarised and coordinates were estimated from accompanying notes using Google Earth Pro. Although published in 1877, the data has never been used before to benchmark data collected more recently by AIMS. (National Library of Australia call number NL 551.56 R963.)

As AIMS data consisted of varying numbers of daily observations, collected using a variety of dataloggers and sensors over variable time periods, averages were calculated for 27 sites spanning the Reef corresponding to the time of the 1877 voyages and mainly at the start and middle of each calendar month. Datasets were analysed as transects using polynomial regression and compared statistically and graphically.

The Cape Ferguson, 1871 and derived AIMS SST datasets used in the study are available here .

Principal findings

Data measured close to shore was contaminated by heat transfers with the landscape. Thus, data for Cape Ferguson (and some AIMS dataloggers, notably several in Torres Strait) was warmer during dry hot summers and did not truly reflect SST.

The Eastern Australian Current warms rapidly from November to December and temperature measured on the journey to Cape Sidmouth in 1871 was significantly cooler than values for the return voyage to Port Stephens. However, despite spatial and temporal uncertainties and within and between year variation in the behavior of the currents, confidence bands for AIMS data averaged for 01 and 15 November overlapped those for the voyage north from Port Stephens and were therefore not different. Within the Latitude limits of where datasets overlap, AIMS data for 04 and 18 December, 01 January and 15 and 01 February, are also not different to data for the return voyage from 13 to 24 December 1871.

Furthermore, toward its northern extremity (Bramble Cay, Latitude ‑9.08o, for which there is no useful AIMS data), while SST increases steadily from 01 November to mid-December, from then until March, SST does not exceed between 29o and 30oC. The curvilinear response evidenced an upper-limit to SST, which is rarely or only briefly exceeded.

Average monthly SST attains a plateau in late November that persists until the cooling phase commences in March. SST in the range 27oC to 29oC from November to late March provides a five-month growing season for corals, which combined with the minimum of around 20oC in July (North Keppel Island) defines the ecotone limit of Reef ecosystems.

North Solitary Island is too cool from September to April (<24oC) for Reef ecosystems to establish and thrive. It was estimated that at Latitude -13.5o , which was the warmest point along the Reef transect, maximum SST occurred in late January to early February (29.64oC ±PI 1.12oC ), the minimum occurred in mid-August (24.26oC ±PI 1.47oC), SST increased to mid-November (27.96oC ±PI 1.1oC) after which the cycle repeats. The interannual range was therefore about 5.4oC. Despite trend in sea-surface temperature being touted as a threatening process that may ‘catastrophically’ impact on the long-term health and survival of the Reef, of the scores of sampling sites operated by AIMS, only several are dispersed towards the extremities of the Reef, while too few are sufficiently well maintained and serviced to provide reliable long-term data.

Sea surface temperatures reported by AIMS are no warmer than they were in November and December 150 years ago in 1871. As solar radiation increases in summer, SST north of Latitude -13.5o is cooled by the monsoon and remains in the range of 29oC to 30oC. AIMS SST data shows no evidence that the process has broken-down or is likely to break down in the future.

As SST has not changed, nor is it likely to change in the future, coral bleaching is due to something else.

Find out more

The page you have just read is the basic cover story for the full paper. If you are stimulated to find out more, please link through to the full paper – a scientific Report in downloadable pdf format. This Report contains far more detail including photographs, diagrams, graphs and data and will make compelling reading for those truly interested in the issue.

Click here for the Full Report with analysis, graphs, tables and photos

[1] Former NSW Department of Natural Resources research scientist.

[2] https://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/our-work/threats-to-the-reef/climate-change/sea-temperature